Even characters who don’t fall into the category of “human” suffer from being “fridged”. Starfire, a character introduced in DC Comic’s Teen Titans in the 1980s, is an alien princess who escaped slavery and joined the superheroes to train to liberate her people. Known for her good looks, sensuality, and naivety, the fascination with subduing strong women took those traits and turned the once strong-willed princess into a physical representation of sexual exploitation, vapidness, and stupidity, even in modern interpretations of the character.

1980 and 1990s

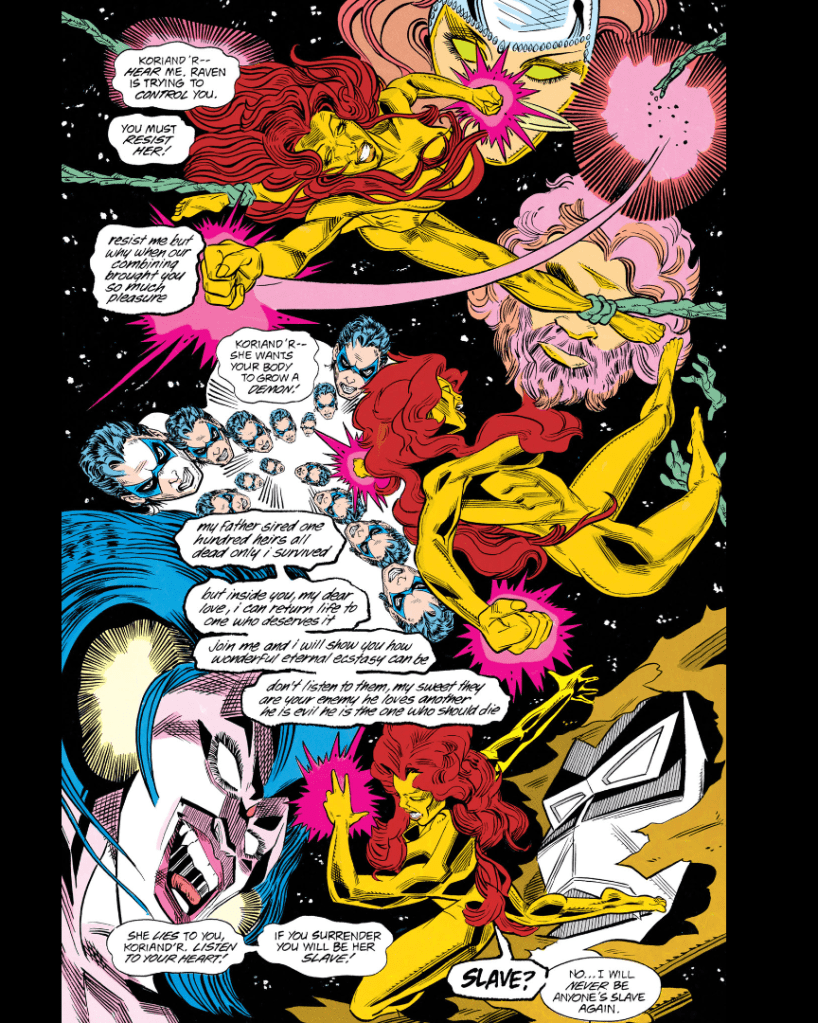

Starfire is a character that embodies the shift of power of censorship after the fall of the Comics Code Authority, an organization created to ensure comics were not obscene. This time is a “particularly notable decade in comics for impossible body proportions with very few clothes to hide them…Furthermore, these characters featured impossibly large breasts and toothpick torsos” (Nelson 2015, 75). For Starfire, her sensuality was based in her unfamiliarity with Earth, as her home planet was ruled by two poles of emotion, hatred and love. Even her learning of English had sensual undertones, as she must kiss Dick Grayson -who was at the time Batman’s sidekick, Robin, to absorb his knowledge of the English language. However, as the powers of the Comics Code Authority faded in the 1990s, the exploitation of Starfire’s sensuality took center stage at the destruction after her wedding to Grayson. Possessed by a demon inhabiting the body of her friend, the demon attempts to impregnate Starfire.

Artfully arranged hair strategically covers Starfire’s figure, yet still allows for her completely nude body to be visible. One of the more important factors to consider in this panel is that it takes place inside Starfire’s consciousness, but her physical body is clothed in the following panels. Her nudity is most likely supposed to be considered metaphorically representative of being unburdened and free of societal standards, while the social hierarchy of her planet actually defines much of the characters backstory. Starfire’s body is bound by vines that then shift towards more traditional alien hands, reminiscent of previous designs of the species that once enslaved her. She breaks free after hearing Grayson telling her that the intent of the demon is to enslave her. While it is hard to differentiate between the two sets of dialogue not directly attributed to a character, as seen on Starfire in the lower right-hand corner, there is subtle differences in the font between Grayson and the demon that would have been more noticeable in the original printing. They have lost some definition in the digitization process. Starfire does not free herself from this violation but is coaxed into doing so by Dick Grayson, a male hero.

Teen Titans Popularity

In the 2000s, Starfire would be represented on the Cartoon Network’s show Teen Titans, and the subsequent spin-off reboot of the series, Teen Titans: Go!. Once again, her relationship with Dick Grayson would be a focal point of her character and character development, although she would be presented in a far less sexualized way.

In the original Teen Titans cartoon, Starfire was the heart of the show. This was fitting as her alien nature caused her to fulfill the very traditional gender stereotypes of cartoon characters by being “more likely to show affection, more likely to emphasize relationships, more helpless, and more likely to ask for advice or protection” as well as being “presented as slimmer, wearing more revealing clothing, having more human-like features, and to be portrayed more often as a team member than a leader” (Baker and Raney 2007, 27-28). Even though her clothes were more revealing than that of the other characters, she was not sexualized or sensual and was portrayed and innocent and sweet.

Relying heavily on the other characters of the show to help her understand life on Earth, Starfire’s naivety often forced the other characters into acknowledging the joy in situation that were not always apparent at first glance thanks to her childlike wonder. This made her popular as “children may be drawn to superheroes not just because of their powers, but also because of the behavior they promote” (Martin 2007, 249). While she leaned on her teammates for support, she also took ownership and power, featuring in storylines about mental health, relationships and communication, and prejudice and racism.

The New 52

Once the popularity of the Teen Titans show had begun to die down, Starfire was once again “fridged.” The power that the character had found was stripped away once again in favor of hyper-sexuality, and left a lot of female fans confused and angry upon seeing the character presented as “little more than a pornographic tableau”(Scott 2013, 15).

Once again, a female hero is at the mercy of a male character and not just battling for the safety of the team. In both the previous header and this image, Starfire is using the same powers. While the 2003 Teen Titans version above is targeted toward a younger audience, there is a massive and drastic difference between the character design. This drastic difference in sexualization is clearly intentional and done to such a degree that leaves the characters nearly unrecognizable as the same character. This version of Starfire finds her body once again on display in a bound position. The neckline of her very limited costume collars her, while the tape-like strips of fabric replace her hair in covering the essential parts of her body. Her body is placed into a curved position, focusing the attention to her chest, hips, and buttocks.

Starfire and Race

(Note: This is once again a section not originally featured in my essay. Instead, I’m taking advantage of my lack of word count to highlight the important discourse surrounding the casting of this character.)

In 2018, DC Comics released streaming series on their app. Included in this was a Titans series, originally developed for cable television. When the casting for this series was announced, Starfire’s casting came under fire. Why? The orange skinned alien princess was being played by a woman of color. Anna Diop, a Senegal-born actress was cast in the role. While some so-called fans were vocal about their beliefs that Starfire’s race not be changed from the start, the vicious racist social media attacks skyrocketed after the first image of Diop in costume was leaked.

While the first season’s costume design choices certainly left much to be desired (a situation not fully rectified until the show’s transfer to the HBOMax streaming platform for the third season) the combination of the hyper-sexuality that is associated with the New 52 Starfire design and the associations of hyper-sexuality, racial exoticism and fetishization, and social economic classism resulted in a multitude of feedback along the lines of “she looks like a hooker”.

The online feedback to Diop’s casting and costuming was seen as pandering to a more “woke audience” and that the inclusion of a person of color playing a character traditionally portrayed as Caucasian was so brutally cruel to Diop that she deactivated her social media accounts, like so many other women in traditionally male-dominated nerd brands, like Kelly Marie Tran of Star Wars fame.

While I could write a whole article on the exploration of women of color by the entertainment industry typecasting them into hyper-sexual roles, in the case of Anna Diop, Starfire, and Titans, there’s been no actual resolution. Instead, the series just kind of turned a cheek, and let Diop handle them on her own.

Starfire’s modern legacy has been defined by the big breasts and long legs of comic book heroines. Her naivety and other-worldliness have become regulated to vapidness and one-note characterizations of comic relief or set dressings, ignoring the character’s long history of fighting for equality, justice, and her people. Instead, her modern legacy fluctuates between the “weirdo” representation in animated series like Teen Titans Go or the hyper-sexed New 52 version of the character, combined with racial attacks on her live-action counterpart, leaving Starfire as a woefully underutilized and under-developed variation of a character with the potential to be one of DC’s strongest and most powerful female role models.

Leave a comment