Regarded as the most powerful of the Amazonians, and the protector of both her race and the “World of Man,” DC Comics character, Wonder Woman is not presented in a consistent way to reflect her strength and power. Described by DC as “beautiful as Aphrodite, wise as Athena, swifter than Hermes, and stronger than Hercules…” her power is immediately reduced to less significance than her beauty (DC Universe 2020) as reflected in her visual representation.

The 1980’s

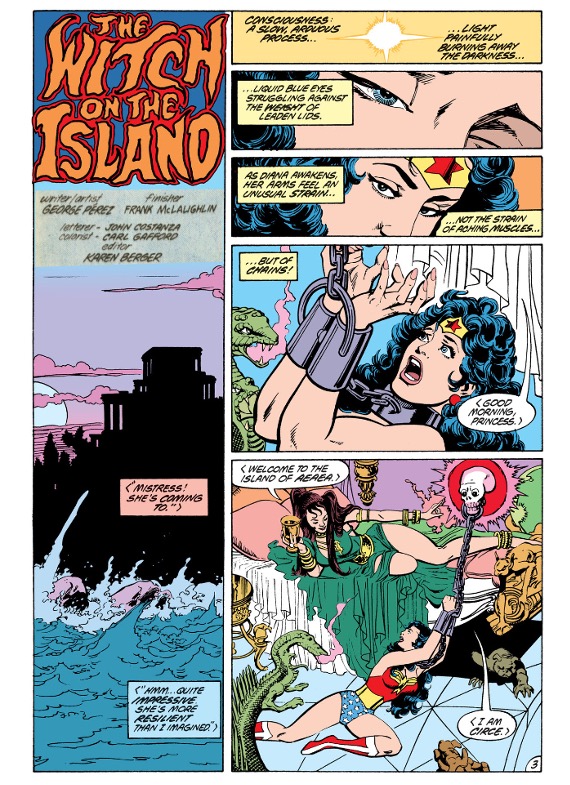

Author’s note: This section covers a very classic version of Wonder Woman, drawn by comics legend George Pérez. I am in no way, shape, or form trying to suggest that George Pérez is anything less than one of the greatest comic art talents of all time. This essay was written in 2020, before he announced his cancer diagnosis, but I’d be remiss in not addressing my deep, deep, deep love and respect for the man here in this more informal version of this essay.

In the 1980s, Wonder Woman was actively placed in what is arguably her iconic image. She featured big hair, big blue eyes, a big chest, and very little costume. The character design of this period is centered heavily in “the affective pull of female vulnerability” (Stabile 2009, 87).

Wonder Woman’s physicality is emphasized in terms of physical beauty standards. The color of her eyes and the visual panel design to create the illusion of her eyes slowly fluttering open create the idea of delicateness and vulnerability. While her muscles, the physical representation of her strength are next mentioned, they are immediately overshowed by the chains in which she is bound in. During this design period, there was little muscular definition of her body, instead focusing on the curvature of her body, here demonstrated by the submissive pose she has been forced into that emphasizes her legs, hips, waist, and chest in a way that mimics the seductive nature of her captor. Carol Stabile asserts that the visual of vulnerability “is used as the grounds for… violence and to legitimize… acts of torture and extreme violence” (Stabile 2009, 87). Creating imagery focused on the submissiveness of the character is excused by the consumer and creator because female characters look appealing to the male gaze in the male dominated base. Breaking down the covers of the Wonder Woman comic in the next decade demonstrated that this trend was far from over as “Wonder Woman [covers] from 1994–1995 showed such poses 41.04% of the time” (Cocca 2014, 419). While this is less than half the time, these statistics reflect Wonder Woman posed in sexually suggestive submissive poses, not including imagery of her bloodied, fleeing, crying, or with groups of fellow heroes, where she takes submissive poses and posture even on the covers of her own books.

The 2000’s

The 2000s ushered in a time of progress certainly established by the recognition and awareness of the WiR theory. Gail Simone, the founder of the Women in Refrigerators website, took over Wonder Woman as head writer with Bernard Chang, an artist of color. It is clear to see the narrative vision of equality and empowerment reflected realistically in the visuals of the characters.

Wonder Woman is reflected 2008 as more realistically proportioned, taller and more muscular than the previous versions. She is depicted in a more powerful stance, highlighting her muscles and strength rather than her curves. Stabile states that “the active roles of both protector and threat are masculinized-strength and power being the foundations of masculinity” (Stabile 2009, 87). In this example, there is a balance between Wonder Woman’s physical strength and power, her masculine features, and the more delicate shapes of her facial structure. Her femininity is also reflected by the young girls who are mirroring and reacting to her stance. Both girls feature softer angles and curves in their hair, clothing, and facial features, while also having muscular definition.

2020

The more recent version of Wonder Woman shows a regression between appearance and story to something more like the representation of the stories present in the 1980s.

Wonder Woman has just crashed her invisible jet, and discovered she has been blinded. Her only companion, and her only assistance, comes from Maxwell Lord, a character known to manipulate and kill to get ahead. While this version of Lord has been helpful and supportive to Wonder Woman, it is not entirely outside the realm of possibility that he will eventually betray her, as the two are often paired as archenemies. This means that this version of Wonder Woman, who features less muscle definition than prior versions, with perfect nails and glossy lips and is curled into a more fetal style position, will be left to support herself in the next issue on the strength of a man whose superpower is, literally, manipulation. In doing so, the writers have once again mimicked the brutality against female characters, as Wonder Woman’s stance is reminiscent of the positioning of Alex DeWitt’s body in the refrigerator, the very panel that began the WiR theory.

Up Next Time: Barbara Gordon, The Killing Joke, and How Feminine Violence Freezes Character Development

Tomorrow’s post is a little different, as I’m no longer restricted by a professor’s word count. So, I’ll be posting the sections of the essay as-is, but also including author’s note about my personal feelings about how feminine violence has limited the character development of Barbara Gordon, including a little bit about my feelings about the DC Animated Universe movie version of that movie.

Spoiler Alert: Even this issue talks about The Killing Joke.

Leave a comment