In Nightwing #90, Babs makes a reference to getting “fridged” when she’s trapped in a refrigerated truck. (Seriously, Tom? You know I love you, man, but oof.) I reblogged a post about how icky it made me feel as a female comics fan and wrote “I could write a whole essay about this… and I have.” That of course, led to requests for that essay. So here’s the Pages and Panels version of my Art History Final? We’ll start today with some background on the Women in Refrigerators, then tomorrow break down Wonder Woman’s growth and design.

Content warning: “Fridging” deals with violent situations, overt/ over-sexualization, and mature themes that may trigger some readers.

Background

In 1999, Gail Simone, a female comics author and artist (and one of my personal heroes), sat down with some of her other female friends in the industry and realized that a “disproportionate number of super-heroines who have been either depowered, raped, or cut up and stuck in the refrigerator,” taking the concept and titling it “Women in Refrigerators” (WiR). This theory was named after the brutal murder of the fictional comic character , Alexandra DeWitt, girlfriend of comic character, Green Lantern Kyle Rayner, who he found strangled and stuffed inside of their refrigerator.

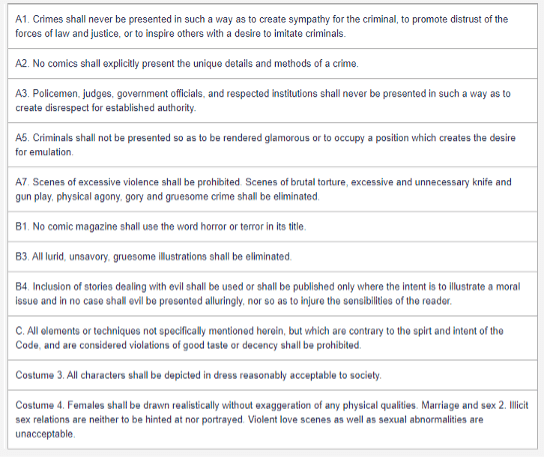

The subsequent investigation revealed a trend in comics of female characters to suffer more significant and violent events versus their male counterparts, the length of time of recovery in story from the event, or in contrast, the lack of attention to the violence in the storylines. These trends pick up in the 1980s, after the end of the Comics Code Authority. The CCA had been designed in the 1950s to ensure that comics were not corrupting the youth of America. This attempt at censorship began to fade in the 1970s, and by the time the WiR concept was created in 1999, nearly all major publishers had turned away from the code’s strict guidelines prohibiting a multitude of acts and ideas.

The strict guidelines gave way to a new era in comic book design that was earmarked by drugs, sex, rebellion, and violence (Chaloner et al 2020). Actions that were once deemed too much for audiences have become commonplace in the style of comic book design and writing since. As the change towards this graphic nature became more commonplace, the fights get gorier, the costumes get tinier, and the female characters got dead-er.

Simone and her peers focused the original Women in Refrigerators theory mostly on female heroes and the wives of superheroes, but the theory can be applied to almost any female character in comics. There has been no formal published study investigating whether or not the industry has made a major change in the portrayal of female superheroes, although some critics cite the increased female representation on page and screen as an example of a “new era of superheroes: The era of the Superheroine” (Nelson 2015). While there has been major shifts in female equality and representation in the major comic publishing houses since the “Women in Refrigerators” website and theory were presented two decades ago, the movement has had little effect on the issues of violence, hyper-sexuality, and gender bias present in the content featuring heroic characters.

The representation of female heroic characters requires a delicate balance. It is important to demonstrate characters in ways that appeal to both men and women, as well as maintain a visual appeal, and support the characterizations created in times that were not nearly as progressive as the current sociopolitical climate, but develop them into characters that combat the stereotypes and archetypes that surrounded this idea. Some of this has been combatted by the inclusion of more female voices creating these stories (Chute 2017). However, as the norm is still for males to be the lead voices and audiences in the industry, progress featuring the violence and sexualization that WiR highlighted is often short lived and reverts back to the norms of brutality and fetishization of female heroes. By examining the design of the female heroic characters of Wonder Woman, the original Batgirl, Barbara Gordon, and the alien princess, Starfire, we’ll discuss the growth and regression of the handling of their storylines and design.

Leave a comment